What Everyone Is Doing: Investing in Early Stage Growth

“Growth rate is the single largest determinant of an early stage company’s valuation multiple.”

– SaaS Capital Research

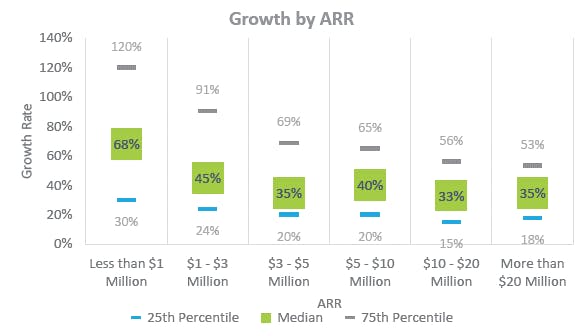

A company’s growth rate is only relevant when compared to a cohort of similar sized businesses. It’s a whole lot easier to be growing 100%+ when ARR is $1mm vs $10mm. Why?

Because as a company scales, its bookings must also continue to grow YoY on a dollar-basis just to maintain the same growth rate. So, it’s no surprise that when we segment by ARR bands, that median growth rates tend to decline over time:

Figure 1:

For companies <$4mm ARR, top VC firms must see triple digit growth to even consider evaluating a potential SaaS investment (i.e. the top 75th percentile and greater).

While Rule of 40 (% ARR Growth + % EBITDA Margin) is widely regarded as the single most important valuation metric, most firms are far more comfortable paying up for growth over EBITDA margin, particularly in early stage businesses:

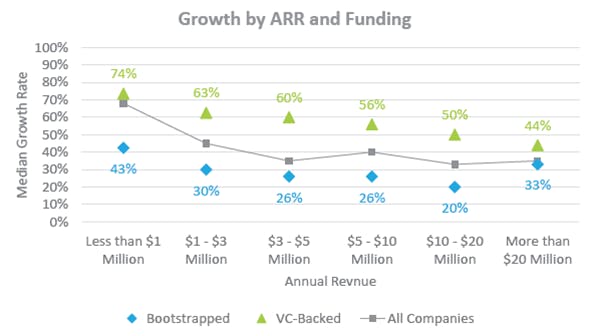

Figure 2:

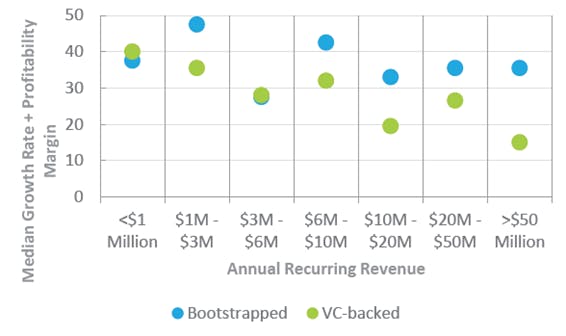

Figure 3:

Figure 2 comes as no surprise – the businesses VCs invest in are, on average, of a higher growth rate than the businesses they do not invest in. But Figure 3, which shows Rule of 40 as opposed to growth rate, tells us that they care so much about finding high growth businesses, that they are willing to look past low profitability/high burn. See how Bootstrapped businesses’ Rule of 40 actually tends to be higher than VC-backed businesses’ Rule of 40.

This reveals two things about VC investing behavior:

1) Growth rate is the single largest determinant of an early stage company’s valuation multiple.

2) In spite of what they may advertise, VCs care less about capital efficient growth than absolute growth.

Investing in Massive TAMs

Investors care more about TAM than entrepreneurs do.

Why?

1) Entrepreneurs that truly believe in their product are typically more confident than their investors that they can penetrate a majority of the market and sustainably rip/replace deals from competitors.

2) While entrepreneurs are busy worrying about hitting 1-2 year budget targets, investors must constantly think of how the next investor will value the business when it comes time to exit (often 5-10 years). And what do you think the next investor will care most about? How the next, next investor will value the business.

Taking VC money tends to pull the future forward. And if a company’s future growth prospects aren’t safeguarded by a massive TAM, VCs will often run from it.

What Everyone SHOULD BE Doing: Investing in Capital Efficiency and Strong Unit Economics over Growth

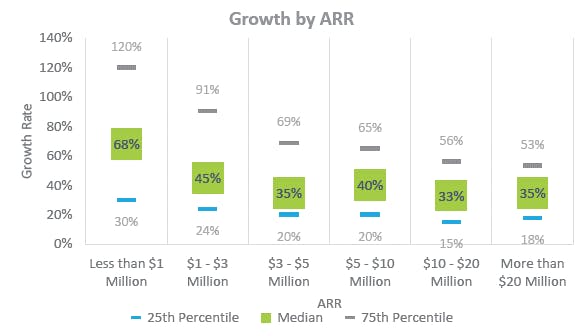

Let’s take a look at Figure 1 again:

Notice how the distribution between the 25th and 75th percentiles tends to shrink over time. Non VC-backed companies (in the 75th percentile and lower) don’t just disappear. In fact, based on Figure 3, they are likely to become self-sustaining, cash flow positive businesses even more quickly than VC-backed businesses. Why?

1) They need to be. Remember that low growth businesses under $4mm ARR are usually not as “hot” in the eyes of investors. So, these businesses will typically have a hard time raising capital at favorable valuations.

2) Most investors reward growth over EBITDA margin.

a. Historically, VCs made their money by investing in growth while private equity firms made their money through financial engineering (i.e. multiple expansion driven by increased scale from M&A, debt recaps, improving margins).

b. In the past decade, an enormous new investor class has emerged, and it's specifically dedicated to running the VC playbook (rewarding growth over EBITDA margin) in businesses too large for VCs. It’s called growth equity.

But based on Figure 3, perhaps rewarding growth above all else is NOT the way to create a healthy Rule of 40 business at scale. What if investors, instead of pumping unnecessary dollars into already high growth businesses’ GTMs, invested in low growth businesses and helped them put in place the processes to become self-sustaining first?

Our two cents: It will take longer to scale a low growth business. But, assuming its unit economics (e.g. retention, CAC payback) are strong, there is no doubt it will “catch up” to the high growth business over time. Remember – no business can stay high growth forever!

To summarize, here are the two paths for investors:

1) Pay 10-20x entry multiples for high growth businesses, help keep their growth rates as high as possible by encouraging burn, and exit at a 10-20x multiple.

2) Pay 2-5x entry multiples for lower growth businesses with strong unit economics and help them grow at a moderate pace for longer while getting to a cash flow positive state. Then, exit at a 10-20x multiple when they achieve scale.

Seems like an easy decision.

- The SeedtoB Team

Are you an entrepreneur innovating in healthcare? Get in touch with our team here.